Fly Fishing Nymphs

Dry fly fishing, since the time of Halford, has been considered the pinnacle of fly fishing. It gets the most attention, it receives the most ink, and dry fly fishermen consider themselves to be pretty snazzy people, in general. But lets take a minute to talk about why fly fishing nymphs is so effective. If trout are calorie calculators, and they are, keep this in mind when they are not spooked or spawning, and not feeding on the surface, they are feeding sub-surface. In nature, as in spam e-mails, size matters. Small things are more likely to get eaten than large things. It is the law of the jungle, and all animals instinctively know this. So trout feed at all times, so that they can grow bigger, and therefore safer. The only reason fish feed on the surface, is because it offers the highest concentration of food at that moment. The moment energy outlay becomes greater than caloric intake, they move to where caloric intake is greater than energy expended. Simple math.

So on to nymphing. It is considered by too many fly fishermen to be a lesser way of going about things. Hence the phrase “Dry or Die”. But I offer this to you. Nymphing is the most difficult method of fly fishing, and once mastered, all other methods of fly fishing become much easier. A streamer is fished on a tight line, so the moment a fish hits, you feel it through the rod. Dry fly fishing, which requires the same dead drift also critical for nymphing, has a visual aspect. When you see the fish eat your fly, you set the hook. But fly fishing with a nymph requires a 3-dimensional presentation. You must have a dead drift, at the proper depth, and you very often cannot see the fly or the fish when using this method. It requires casting technique, line control, and the ability to sense a take through subtle movements in the line or leader. Or the use of an indicator. Which is fly-fishingese for a bobber. Fly fishermen don’t use bobbers- bait fishermen do. We use indicators. And don’t kid yourself, they work.

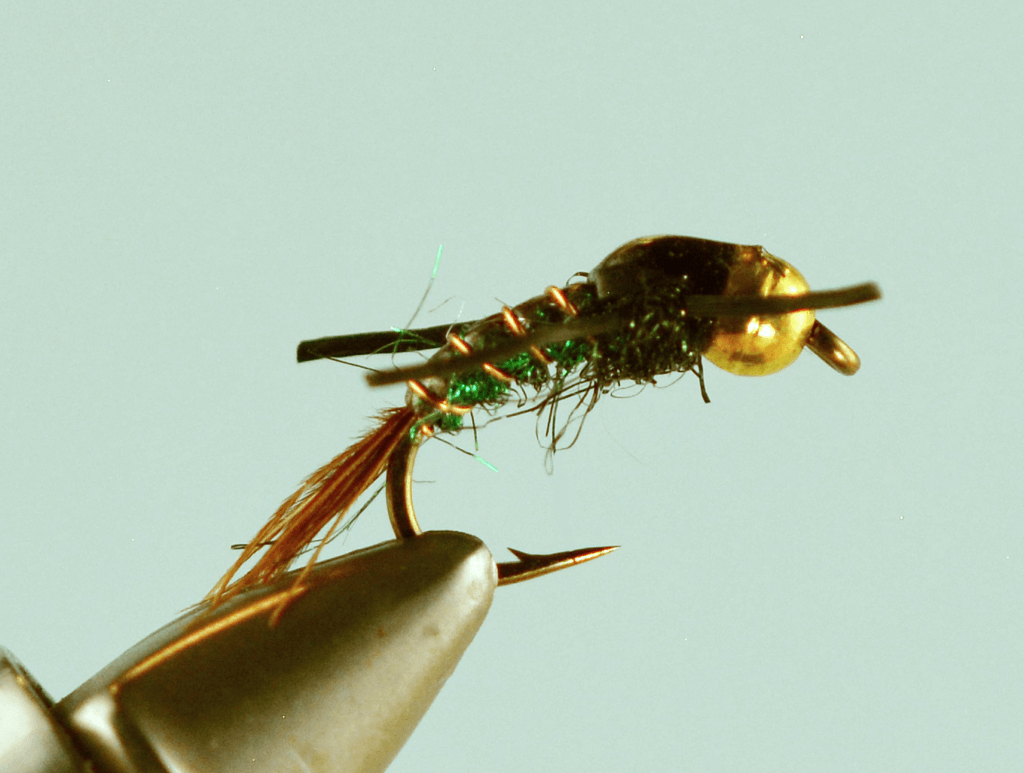

Flies For Nymphing

So you’ve decided to nymph, and you want to know what fly to use. Well, for our fly fishing purposes, we will call nymphing the use of any sub-surface fly utilizing a dead drift technique. So it will include San Juan Worms, sunken ants, beetles and hoppers, and any other insect that is below the surface, and can’t control its destiny (can’t swim). So you go to the hatch charts, and see what is going on when you plan to go fishing. And then go look at the info on the hatches that will be available at that time. So now you have that knowledge.

So what to do with that knowledge? To start, remember that nature does not allow for wasted space. If your chosen bug is the Western March Brown, you know that as a dry fly it is 14mm long, or a size 12 hook. Knowing that, you can be pretty sure that the nymph will also be 14mm long. Nature does not allow for a 28mm nymph to hatch into a 14mm fly. The insect could not afford the energy to support such a large casing for so small a filling. In the same vein, a 7mm nymph will not hatch into a 14mm adult. You just can’t cram all that insect into such a small case. So you can choose a nymph in the same length as the dry fly, and be pretty sure that you are close to matching what the fish are seeing.

Also, a brown insect rarely hatches from a non-brown casing casing. There are exceptions to this, but it is safe to say that if the adult (hatched) insect is brown, the nymph will also be brown. It may be darker, or lighter, but the color will be close to the same as the dry. Follow this rule of thumb, at least until the fish prove you wrong. Which they will, on occasions too numerous to count.

There is another thing to consider while nymphing. When fish are actively feeding on the surface, they are there for the density of insect life present. And most of the time, they are focused on one specific type of insect, because more often than not, the insect density is caused by that one type of insect following its biological clock and moving to the surface to hatch. And if there are enough of those insects, the trout may in fact focus on specific stages of those insects, such as spinners, or cripples, or emergers. But that is not normally the case when nymphing. Because fish are continually feeding sub-surface, there are many times that they are not keyed into any one specific type of insect. And because there are so many different insects in that water at any given time, and they are all crawling around on rocks, and feeding, and being swept away in the current and appearing to the fish, a trout feeding sub-surface will usually take a well presented nymph of a basic size and shape.

Which brings us to this point. The life cycle of mayflies, caddis and stoneflies follow very specific patterns. Most mayflies and caddis flies follow a one year life cycle. So again let’s use our friend the Western March Brown (WMB) to illustrate this point. The WMB is 14mm long, and hatches in April. An average female lays approximately 2000 eggs, which sink to the bottom and hatch. If a 14mm bug lays 2000 eggs, one thing we know about these eggs is they are small. Really small. And when they hatch, they are of no food value to the trout- they are too small to be noticed or eaten. They are an important part of the food chain, but not to the upper end of the food chain, where our interest lies. So let’s jump ahead 6 months, to October. Many, many of those tiny nymphs have not survived, but the ones that have are now approximately 7mm long, or about a size 16. They are now large enough to be of value to the trout, and the trout are eating them when they float by.

Keep in mind that this is occurring for every species of mayfly and caddis in the river. They all lay a lot of eggs, and as the nymphs grow and grow, they become more and more important as a food source to the trout. So let’s look at this. If you are a trout, and looking for a recognizable food form, a small mayfly nymph will always be a viable choice, because somewhere in the river, at almost all times, there is a size 16 or 18 mayfly nymph or caddis worm present. This is a food form the trout sees all the time, and will take readily at any time.

It is even better for stoneflies. They follow a 2 or 3-year life cycle. So let’s take our friend the salmon fly as an example, which follows a 3-year life cycle. They are approximately 48mm when they hatch, so that means at hatch time, there is a crop of 48mm nymphs (mature and hatching), a crop of 32mm nymphs (2 year olds) and a crop of 16mm nymphs (1 year olds). What this means is that at any given time on any of our local rivers, there is a stonefly nymph of approximately 14-20mm long floating around. Always. How old they are depends on what time of year it is, but they are always available. That’s a nice fall back position. If there is nothing discernable going on, it is never wrong to fish a size 16 mayfly nymph or a size 10-12 stonefly nymph. It may not be the most right thing to do, it may not be what the fish are keying on, but it is never wrong, and that is a good thing to know when at a loss for choosing a fly.

Which brings us to another one of our friends, the San Juan Worm. The poor, maligned San Juan Worm. If only someone had named it the San Juan Annelid, we would be happily fishing this incredibly effective fly, and never think twice about it. But use the W word, and it just rubs a fly fisherman the wrong way. But the San Juan Worm is a representation of a water based tubeflex worm, an annelid, and they are present in the water 365 days a year. It is a continually recognizable food form to a trout, and as they are available 365 days a year, they are eaten 365 days a year. Not bad, a fly for every day of the year.

How To Fish Nymphs

So let’s talk about the actual nymphing for a minute. Nymphs live amongst the rocks. And rocks live on the bottom. Ergo, nymphs live on the bottom. Seems pretty basic, but it needs to be said. So, in order to properly imitate a nymph, you need to be close to the bottom, where most of the nymphs are. The fish want to be near the bottom anyway, where the water is typically moving slower and the trout are using less energy. A convenient set-up for the trout; food and less energy exerted staying where the food is. So it is important to get your fly near the bottom. Because that is where the fish, and the nymphs, are. And they are not apt to move very far for your fly, because they don’t want to expend the energy. In warmer water, trout may move further for your fly, but it is a good bet that you will need to get your fly right on the bottom.

So your focus on nymphing is to get your fly as close to the bottom as you can. And truthfully, an indicator can often be a deterrent to this. Conventional wisdom states that the indicator should be set above the fly at 1 ½ times the depth of the water. The 1.5 depth ratio is because your fly does not hang directly below the indicator, but comes off at an angle. So in 2 feet of water, you should set your indicator at three feet. And the indicator works, and works well, as long as you fish at that depth or in a lesser depth. But as soon as you move to deeper water, your nymph is not near the bottom. And so it is less effective. One of the things we recommend when fishing deeper is to set your indicator as far from the nymph as you are comfortable with. We will often place our indicator around 5-7 feet from our nymph. This will allow the nymph to get deeper, and that means that you have to adjust the indicator less. What you lose is some immediate contact with the nymph when it is taken. (Because there is a longer piece of mono between the fly and indicator, it takes longer for the piece of mono to tighten when registering that the drift of your nymph has been interrupted.) But what you gain is that your fly, at some point during the drift, will be near or on the bottom. Which is of course where the fish are. And that is the point. All nymphing techniques, and this is only one of many, should provide a way to get your nymph to the bottom in deep water and keep it there.

Hopper/Dropper

Strike indicators are a very effective way of fly fishing a nymph. They allow us to easily visualize the take underwater by acting, basically, as a bobber. One of the most popular methods of nymphing is the hopper/dropper, which is a dry fly with a nymph tied off of the rear. The best way to do this is tie a clinch knot to the bend of your dry fly, and then tie your nymph off that. A few things come to mind. Always use a lighter test mono off the bend of the hook than you are using as a tippet, so if you hang up your nymph, you don’t lose both flies. And remember to shorten your leader before attaching the dropper. Attaching a 3’ dropper to a 10’ leader gives you 13’ total with a hinge point in the middle- not the easiest rig to cast. Shorten up your leader so that you can easily control your cast, and keep your tangles to a minimum. And remember, don’t try and place a size 8 nymph off of a size 16 dry fly- the dry won’t float. So always use a larger dry fly than your nymph. And you don’t have to use a hopper, a large stonefly or even a big parachute fly will also work.