Yes, the fly rod did begin as a stick. It was a well chosen stick, flexible with butt strength, but that didn’t stop it from being a stick. What passed for line was tied to the end, and off they went. By the late 1400’s, rods were still being built from sticks, but separate stick sections were spliced together, in order to get the action required. The tip came from the center of a tree, for flexibility. They could be anywhere from 10-15 feet long, and were heavy. The line was still tied to the tip.

Rods continued this way until the arrival of Tonkin cane from China. While Tonkin was initially used in its hollow state, craftsmen soon discovered the culms could be split, and the first rods that could actually cast were born. Split cane forced the development of longer lines, reel seats and reels, more permanent handles, ferrules and guides. It was the first modern fly rod. The cane could be planed or sawn to create specific, reproducible tapers and opened up many new vistas for fly fishing.

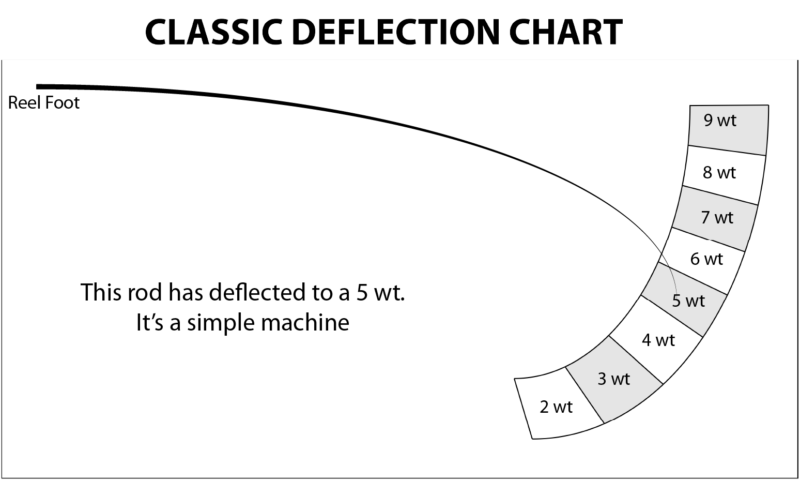

Yes, some cane rods re worth $1,000’s of dollars. 99.9% are not. Valuable cane rods were hand planed to within 1/1000” tolerance. The vast majority of cane rods were cut with a saw, with much less accuracy. When AFTMA set the standard for fly line weights (Fly Line), they created a deflection chart to help anglers identify the proper new line weight for their rod. Utilizing a wall mounted reel foot and a known weight, the rod was mounted on the reel foot, and the weight clipped to the tip top. The rod would deflect, and the tip would land within a region on the chart, giving a line weight for the rod. The first diagram shows a deflection chart, the second shows a rod deflecting to a 5 weight line.

Cane was the best and preferred material for rod building until 1945 when technology developed before and during the war effort found its way to fly fishing. While fiberglass was introduced earlier as a solid blank, modern rod building began in ‘45 with the advent of the initial hollow fiberglass fly rod. For the first time, rods were tubular, and manufacturers had to develop brand new criteria for building and controlling action and taper.

There are two variables in rod design, the materials resistance to bending, described in terms of modulus in millions, and the diameter of the hollow tube. Fiberglass is a very low modulus material, meaning it has very little resistance to bending. Fiberglass itself is a very flexible material. Diameter is best understood this way. If you took a 9’ long, 1/16 inch steel pipe and shook it, it would bend quite readily. Take that same piece of steel and hammer it out to a 4” diameter, and it would lose most of its flexibility. Now the design conundrum comes in. How much material is needed, and at what diameter is it needed.

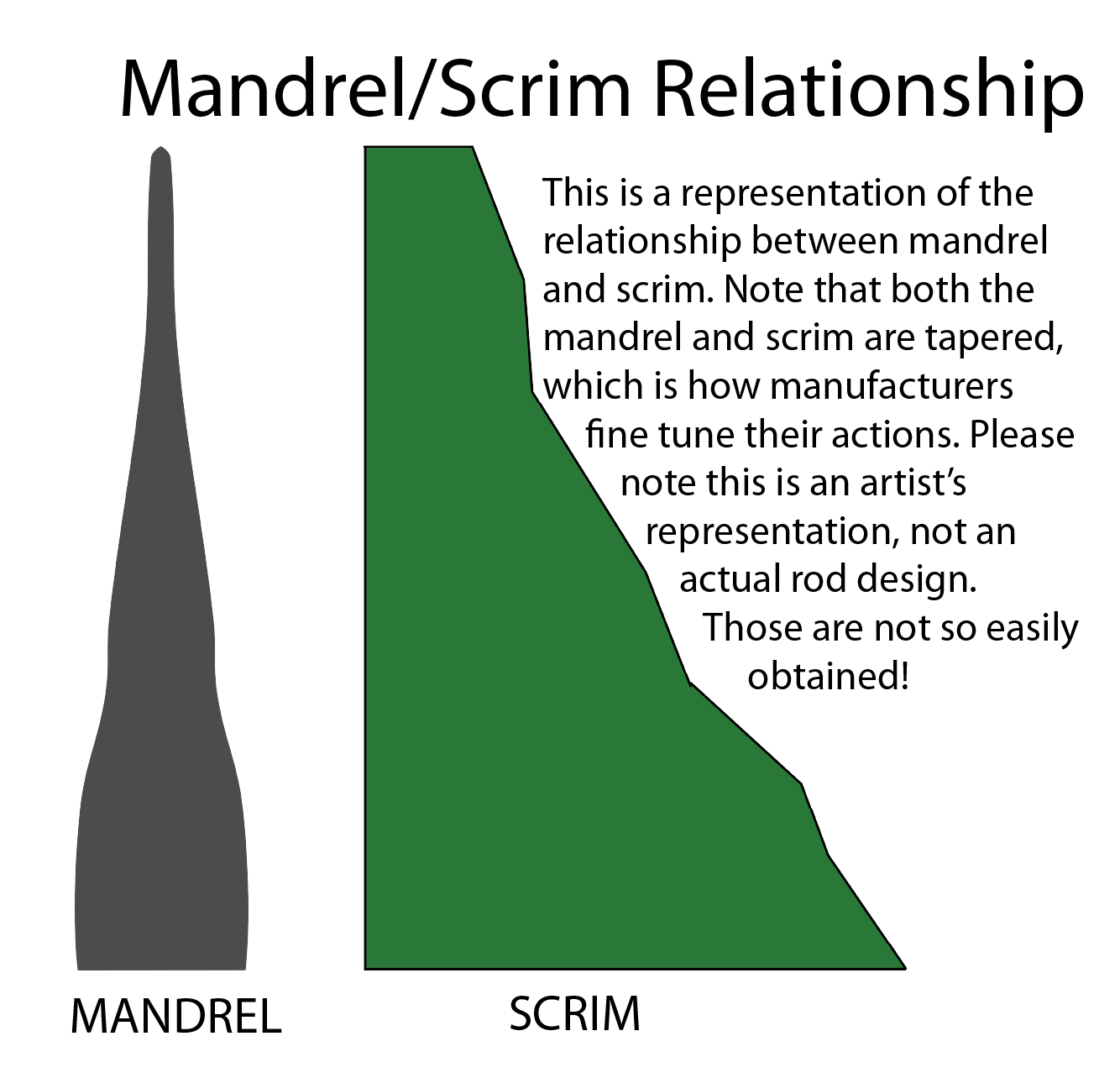

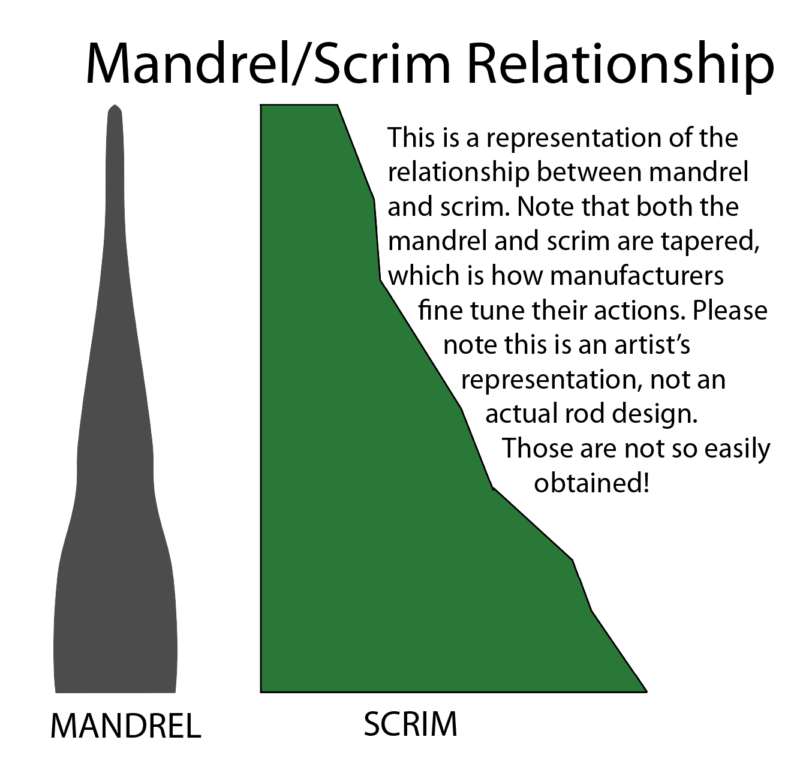

The manufacturing process of hollow fly rods evolved this way. The mandrel- a solid rod varying in diameter along the length- is milled, and used to control the inside diameter of the rod. The fiberglass scrim (sheet of fiberglass) is also cut in a taper as well, and then coated with resin or adhesive. The scrim/adhesive is wrapped around the mandrel, then rolled on a rod rolling machine under a lot of pressure to compress, shape and complete the process.

The diagram above is a simplification of the scrim/mandrel interaction. Notice there is less scrim at the top than the bottom, matching to the thinner tip of the mandrel. Less material over a thinner diameter provides flexibility, needed at the tip. As the diameter expands and more material is added, the rod gets stiffer as it goes to the butt section. How the rod will flex- deeply, or very little- is defined by this combination of diameter and material.

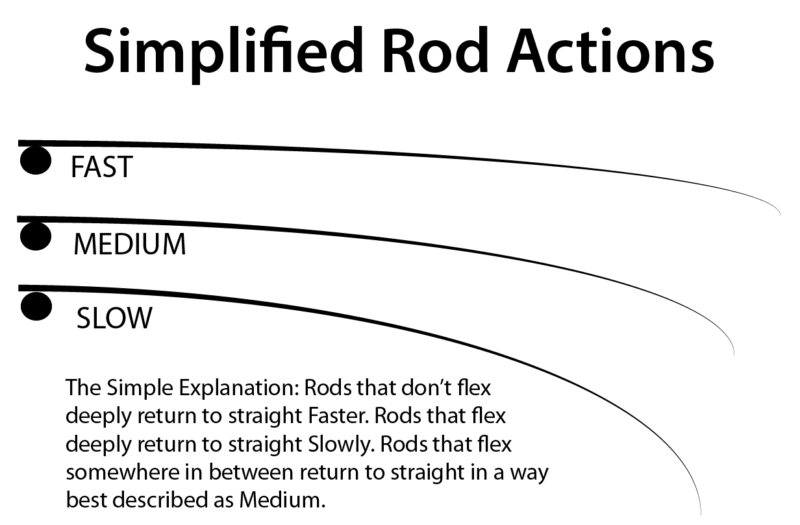

The above diagram is a simplification of flex patterns of fly rods. In the terminology of fly fishing- slow action, medium and fast action. There are variations and combinations of this found in every manufacturer of rods in the past and today. It’s important to know about action, so you can decide which action is best for you and your casting. YOUR CASTING. It doesn’t make any difference what anyone else thinks is a good action, if you don’t like it it’s not correct for you. This applies to the oldest cane rods and fiberglass as much as the most modern graphite fly rod available.

In 1973, the Orvis Company introduced the first graphite fly rod, and changed the face of fly fishing. Graphite has a much higher modulus than fiberglass, meaning it’s a stiffer material. Since its advent in the 70’s, graphite technology has continued to advance, and modulus has increased. If I remember correctly, the first graphite rods were about a 25 modulus. Now manufacturers are using graphite with modulus of over 80. This has provided such a wide range of actions, rod weights and strength, along with durability, as to be almost unrecognizable from its origins.

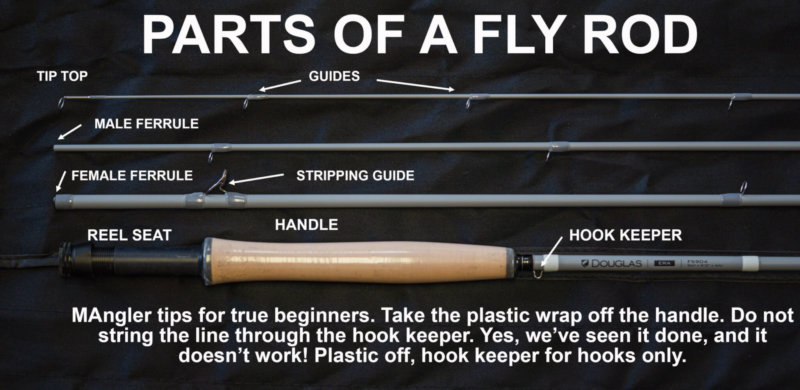

Due to the weight of cane and fiberglass, rods were shorter in their initial design. The modern graphite fly rod can vary in length from 6-15 feet in length, with the industry standard being 9’. Shorter rods are often used on smaller waters, while the longer rods are used to enhance mending and distance, as well as specific casting styles like spey casting. The longer rods often require two hands from the angler, and can attain tremendous distance when casting. Rods are designated by line weight, length and number of pieces. The industry standard for trout today is a 9’, 5 wt, 4-piece fly rod.

Graphite has opened up whole new vistas of fly fishing. 10-15 weight rods are now light enough to be castable, opening up the salt in ways not contemplated previously. Graphite ferrules are so smooth that 4-8 piece rods are not only available, but excellent casting tools. This changed the way we travel with fly rods, as well as opening up the back country and making bicycling with a fly rod much safer.

Graphite also revolutionized the action of fly rods. While modulus can be described as resistance to bending, another description is a more rapid return to straight. This has opened up amazing new avenues of action. As modulus increases, we are leaving simple fly rod actions as shown in the flex pattern diagram and getting into more complex actions. With high modulus graphite, manufacturers can create a deep flexing, relatively fast action fly rod. The higher mod graphite returns to straight more rapidly- so even with a traditional “medium” flex action, the graphite itself is faster. The rod returns to straight faster, creating a relatively fast medium flex rod. This type of compound taper was unachievable without graphite.

As tapers expanded with higher modulus, manufacturers continued to refine their tapers in lower modulus rods as well. Lower modulus graphite is less expensive to use, and as mandrels pay for themselves the creation of high quality, less expensive rods has become the norm, not the exception. With such a disparity in price in rods, even from the same manufacturer, what makes a rod more expensive?

As previously stated, the higher the graphite’s modulus, the more expensive it is. Component quality can vary. Some reel seats are Nickel Silver with exotic wood inserts, some are aluminum. Cork handle quality, rod tube and sock style and other costs vary. The time of build comes into play, with guide style and finish coats adding to costs. But the real cost of a fly rod is unseen.

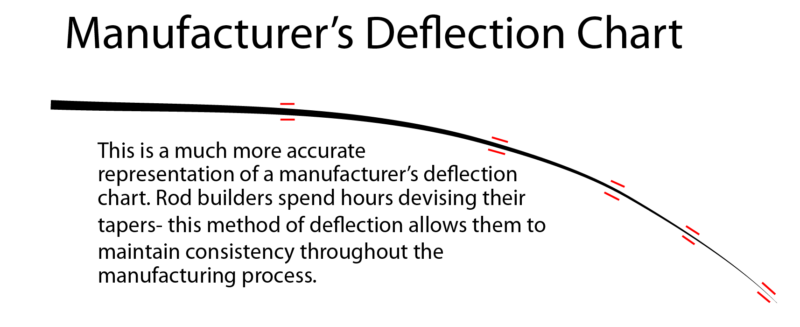

When I toured the Sage Rod factory, I was amazed at how many pieces I saw broken in the short time I spent in the construction room. They had a machine for crushing unsuitable blank pieces. Look at the diagrams below.

While the rods in the first diagram are both 5 weights, they are going to cast significantly differently. It’s consistency that creates the greatest cost in fly rod manufacture. The second diagram shows how most fly rods are deflected by the manufacturer. There are incremental zones the rod must fall into to become a fly rod. The wider those zones, the more pieces can be used. The narrower the increments, the more consistent the action, and the more pieces are unusable. Once rolled, the graphite can’t be reused. It’s a dead loss, and needs to be paid for. It’s the most expensive part of high end fly rods, the pieces that don’t work and end up crushed and useless in a trash can.

To sum things up, if you buy a rod from a known fly rod manufacturer, it’s almost impossible to find a bad one. It might not be magic, but it won’t be awful. After A River Runs Through It, fly rod manufacturing, graphite construction and taper design went through the roof. Increased sales provided more funding for R&D, with fly rod actions improving exponentially. They continue to improve on a yearly basis. In 1985, when I started selling fly rods, I could say if you don’t spend $400 on a fly rod, it really won’t be any good. Now, it’s a bald faced lie to say if you don’t spend $1200 on a fly rod, it really won’t be any good. We sell fly rods for $89 that outperform any rod available in 1985. We are living in the golden age of fly rod design. Rest easy in your rod selection- it’s all good.